Mar 21

2024

On the Run: Rogue Heroes—Awaken your powers and save your friends!

Posted by: K L | Comments (40)

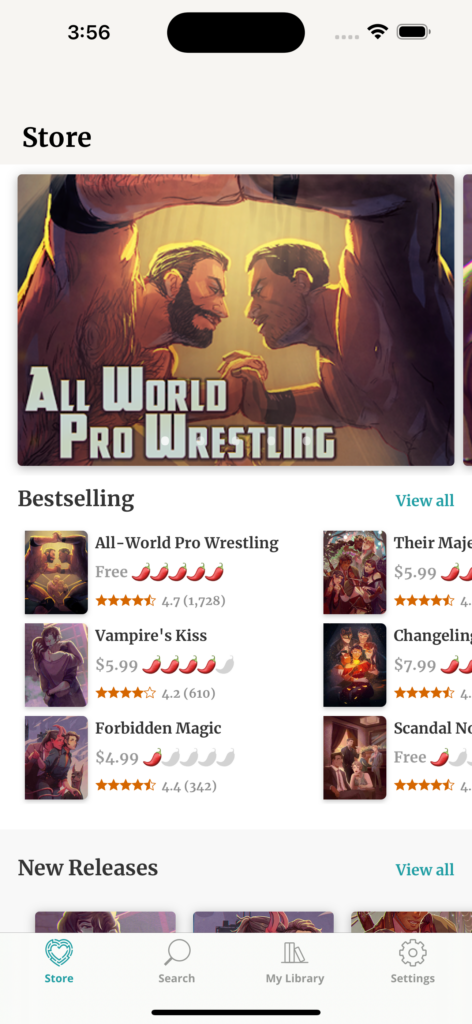

We’re proud to announce that On the Run: Rogue Heroes, the latest in our popular “Choice of Games” line of multiple-choice interactive-fiction games, is now available for Steam, Android, and on iOS in the “Choice of Games” app.

On the Run: Rogue Heroes is 33% off until March 28th!

Awaken your powers and save your friends! Uncover the secrets that the military has been hiding about Activated people, about your family, and about you.

On the Run: Rogue Heroes is an interactive teenage-superpower novel by Alyssa N. Vaughn. It’s entirely text-based, 200,000 words and hundreds of choices, without graphics or sound effects, and fueled by the vast, unstoppable power of your imagination.

For decades, everyone with special powers like super-strength or flight has been forced into lifelong conscription in W.I.N.G.S.: the Weaponized Individual National Guardian Services. Most of this military branch’s activities are secret—except for the daring exploits of heroes like Ms. Midnight, Phantom Phaeton, and Sergeant Smash.

You and your older sister grew up living with your grandmother, who cared for you, provided for you, and sheltered you from the truth. She knows what they do at W.I.N.G.S., she knows what happened to your parents, and she knows about the deadly genetic disease that you and your sister both carry.

Now, you and your sister have finally Activated your powers, W.I.N.G.S has arrested and conscripted your sister, and you’ve fled with your grandmother, on the run from psionic government agents with abilities just as powerful as yours.

But you’re not alone! There are people out there trying to fight back against W.I.N.G.S., people who could be your friend—or more than friends. There’s Micah, a long-lost friend with shoulder-length locs and a big secret to protect. Alex, a pickpocket/con-artist has illusion powers and a lot of eye makeup. Then there’s Knockout, a vigilante with a red-brown ponytail and homemade costume, including a mask and cape.

While your scrappy little group races against time to save your sister and yourselves, your own powers are growing stronger every day. Outrun cars on the highway with super-speed, pull down telephone poles with your super-strength, let out supersonic cries that can shatter glass—or just turn invisible and sneak away from it all. You’ll need every bit of your power and your smarts as you uncover secrets that could change the lives of every Activated person on earth.

• Play as male, female, or nonbinary; gay, straight, bi, or asexual.

• Choose your portfolio of powers: super-strength, super-speed, heightened senses, supersonic shouts, or invisibility!

• Befriend or romance a childhood sweetheart, a scrappy con-artist runaway, or a powered vigilante with big golden-retriever energy.

• Discover the truth about your family and rebuild your relationship with your long-lost mother—or leave it all behind and seek support only with your friends.

• Fight back against the government’s control of Activated people, join their secret organization and become even more powerful yourself, or make peace between opposing factions.Who will you trust? Who are your parents? Who will you date?

We hope you enjoy playing On the Run: Rogue Heroes. We encourage you to tell your friends about it and to recommend the game on Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and other sites. Don’t forget: our initial download rate determines our ranking on the App Store. The more times you download in the first week, the better our games will rank.

Steam

Steam Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Tumblr

Tumblr RSS Feed

RSS Feed